Responding to the Campaign to Ban Reversal of Mifepristone in Colorado

Efforts by abortion proponents to outlaw progesterone therapy after mifepristone consumption are not based on science or good medical ethics.

Summary

- The state of Colorado recently passed into law a bill that would ban medical professionals from presenting progesterone therapy to patients as an option for reversing the effects of mifepristone should they change their minds after ingesting that drug to induce an abortion.

- This therapy, also known as “abortion pill reversal” (APR), is a relatively new but promising treatment that has already saved the lives of thousands of babies after an attempted abortion.

- Attempts to characterize APR as unsupported or unsafe are profoundly deficient or even dishonest.

- It is a breach of medical ethics to legally mandate that medical professionals deny patients information that may allow them to prevent the loss of a wanted pregnancy.

Background

Abortion pill reversal (APR) refers to the use of natural progesterone to counteract the abortive effects of the drug mifepristone, the first in the two-drug regimen most used in a chemical abortion procedure. This treatment, which has been used for about a decade, offers pregnant women who have begun a chemical abortion but changed their minds a chance to keep their pregnancy and deliver a healthy child.

- A significant number of women change their minds after starting a chemical abortion protocol; the Abortion Pill Rescue Network (APRN) reports receiving an average of 150 calls per month to their hotline for women who wish to access APR treatment.

- APRN also reports that over 4,000 babies have been born alive after their mothers were given progesterone therapy following mifepristone ingestion.

- The largest case series examining the efficacy of this treatment to date found a successful reversal rate of 64-68% in the most effective protocols.

APR has been subject to critique by pro-abortion medical organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Abortion proponents in Colorado, claiming that this treatment is “unscientific” and potentially unsafe, have passed a state law that would subject medical professionals to sanctions for “professional misconduct” if they present APR as an option to abortion patients unless the state’s medical, nursing, and pharmacy boards all rule that the treatment is the medically accepted standard of care. As will be shown, not only are critiques of APR’s scientific grounding thoroughly deficient, but also, informing patients who are considering an induced abortion of this option should be a part of standard medical care.

Evidence Supporting APR

Contrary to the claims of APR’s opponents, the treatment is backed by multiple levels of evidence: biologic logic, animal studies, retrospective case series, and more.

Biologic Logic: How APR Works

Whereas mifepristone blocks the effects of progesterone in a woman’s body, thus depriving the embryo of the uterine environment necessary for survival, administering progesterone may mitigate mifepristone’s effects and prevent the embryo’s death.

It’s important to note that the theory behind progesterone outcompeting mifepristone at the level of the progesterone receptor stems from a rather basic principle in biochemistry. As Elsevier’s Integrated Review Biochemistry states, when a competitive inhibitor ‘competes’ with a substrate to bind to an enzyme and render it inactive, “adding more substrate will yield more of the active enzyme substrate form”.1 Mifepristone is a competitive inhibitor that blocks the substrate progesterone from binding with receptors. Per this commonly understood biological phenomenon, introducing more natural progesterone allows it to outcompete mifepristone.

Animal Studies

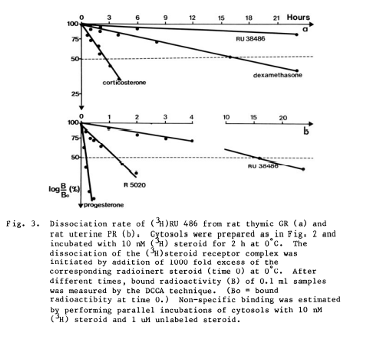

- A pharmacokinetic study published by the original manufacturer of mifepristone, Etienne-Emile Baulieu, not only demonstrates clearly that mifepristone binding can be overcome by the presence of progesterone but also presents in the graph below the rate at which it can be removed from progesterone receptors in the presence of high concentrations of progesterone in rat models.2

- A 1989 study on pregnant rats found that 100% of the subjects that were given mifepristone and then progesterone delivered live offspring, compared to only 33% of the subjects that were given mifepristone alone.3

- A 2023 study examining the progesterone-mediated reversal of mifepristone-induced abortion in a rat model found an 81% successful reversal rate, compared to a 0% ongoing pregnancy rate in the mifepristone-only control group.

Case Series

There are three peer-reviewed retrospective case series that have tracked ongoing pregnancies after progesterone administration following mifepristone ingestion:

- Delgado et al 2012, a small study of six women who used progesterone after taking mifepristone, four of whom went on to have live births of children without malformations4;

- Garratt & Turner 2017, another small study, found that two out of three women that had attempted a mifepristone reversal with progesterone achieved live, healthy births5; and

- Delgado et al 2018, a much larger study of 547 women, that found that intramuscular or oral administration of progesterone within 72 hours after taking mifepristone yielded a 64-68% survival rate (respectively) of a pregnancy through 20 weeks’ gestation.6

Randomized Controlled Trial

A 2020 prospective trial by Creinin et al attempted to examine the safety and efficacy of mifepristone reversal with progesterone but had to be halted early due to safety concerns when 3 of its participants presented to the emergency room with bleeding. This was a randomized placebo-controlled trial of Mifeprex alone (control) vs Mifeprex plus progesterone. It involved a total of only 10 analyzable patients: 5 in the Mifeprex alone arm and 5 in the Mifeprex plus placebo arm. This study has been grossly misrepresented by APR detractors, as will be detailed in the “responding to critiques” section below.

Other Evidence

Notably, ACOG’s own Practice Bulletin 225 on medication abortion recommends that women taking mifepristone refrain from taking depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), a progestin-only birth control, on the same day on the grounds that it increases the risk of an ongoing pregnancy.

Is APR Safe?

Strong support for the safety of APR comes from the following considerations:

- Natural progesterone has been routinely and safely administered to women for over 50 years, as the standard of care for patients who become pregnant via in-vitro fertilization10, as well as to supplement progesterone deficiencies in early pregnancy.11

- A large 2019 placebo-controlled trial of more than 4100 women with threatened miscarriage showed no safety risks of administering natural progesterone.12

- The case series listed above found preterm birth and birth defect rates comparable to that of the general population.

Responding to Critiques of APR

The most common critiques of mifepristone reversal were summarized in a statement by ACOG, in which the only studies addressed were the three case series listed above and Creinin 2020. Of the former, ACOG falsely claims:

- That they were not supervised by an institutional review board (IRB) or an ethical review committee, “raising serious questions regarding the ethics and scientific validity of the results.” ACOG and any research scientist is well aware that retrospective chart reviews are routinely exempt from IRB approval, and all three of the above studies were retrospective chart reviews. But ACOG is even more egregious to claim no IRB involvement in these studies when in fact, Delgado 2018 clearly states: “The study was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board.”

- That they lack a control group. These studies utilize a historical control, which, ironically, is exactly the same kind of control that was used for the FDA approval of mifepristone. Historical controls are a standard practice in cases where placebo control would be unethical. In each of these studies, using a placebo control would require administering a placebo to women who had requested treatment (one that has biological support of its effectiveness) to prevent the termination of their pregnancy and the death of their child in utero. This would be unethical. Delgado’s large retrospective case series used the historical control of embryo survival rate after mifepristone alone, which was published in a previous systematic review that analyzed outcomes of every study ever published in which women took mifepristone but not misoprostol to terminate a pregnancy. This review found a continued pregnancy rate of between 10-23 percent. Delgado et al used the highest possible survival rate of 25 percent for their comparator number, thus minimizing the overstatement of his results.7

- That safety outcomes were not reported. Delgado 2012 and 2018 clearly document the most important safety data points – preterm delivery and birth defects – to track any negative effects of mifepristone reversal by progesterone on fetal development. Delgado 2018 found a preterm birth rate of 2.7% compared to approximately 10% in the general population, and a birth defect rate of 2.7% compared to 2-5% in the general population. No other adverse obstetrical outcomes were noted.

It is undeniable that these studies have limitations, from a small sample size to the inherent weaknesses of retrospective case series compared to prospective studies. But none of these limitations render them scientifically invalid; rather, they add new pieces to a developing body of data and give direction for future research.

ACOG also suggests that Creinin 2020 raises concerns about the safety of APR. This is a blatant misrepresentation of this study’s findings. Here is what the study found:

- In the arm that received Mifeprex alone, 2 patients (2/5=40%) completed their abortion without complications. 1 patient (1/5 = 20%) had a living embryo 2 weeks after treatment and 2 patients (2/5=40%) had ER visits for hemorrhage. Both patients who were taken emergently to the ER required a D&C to control the hemorrhage and one required a transfusion, for a transfusion rate of 20% (1/5=20%).

- In the arm that received Mifeprex plus progesterone, 4 patients (4/5=80%) had a living embryo at 2 weeks after treatment. One patient was transported to the ER for hemorrhage, but by the time she got to the ER, the bleeding had stopped, she had completed her abortion and she received no treatment.

- ACOG notes that this study “was ended early due to safety concerns among the participants”, which many have taken to mean that there were concerns for the safety of the subjects taking progesterone after mifepristone. This was not the case. To the contrary, the safety concern was in the arm of women given just mifepristone, not in the arm given progesterone.

- In fact, what the Creinin study showed (though its small numbers preclude statistical significance), in a double blinded randomized controlled design, is that progesterone given after mifepristone is not only safe but is also highly effective (4/5 = 80%) for embryo survival.

In addition to the above critiques, it has been claimed that the 4,000 reported successful reversals can be explained by the patient’s decision not to take misoprostol, the second drug in a chemical abortion protocol, rather than the use of progesterone. This claim is supported by a 2015 systematic review examining the continuing pregnancy rate of women who attempted an induced abortion by taking only mifepristone, which states that it found a continuing pregnancy rate of 8-46%. However, this study fails to distinguish between an incomplete abortion (in which the embryo or fetus may not be alive, but the pregnancy tissue has not completely passed from the woman’s body) and a continuing pregnancy (in which the embryo or fetus is still alive). A 2017 systematic review that does distinguish between these two outcomes finds a 10-23% ongoing pregnancy rate after consuming mifepristone alone, which is much lower than the documented success rate of APR.

Ethical Considerations

It is important to base clinical and public health decisions “on the highest quality scientific data that is derived openly and objectively”, as the CDC states. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard of scientific studies due to their ability to limit bias. However, as former CDC Director Thomas Frieden states, “many other data sources provide valid evidence for clinical and public health action”13, and drugs and treatments that aren’t backed by RCTs are recommended by clinicians to patients every day.

Many factors come into play when deciding whether a treatment is sufficiently well-supported to justify moving forward with it, such as the potential cost to a patient of forgoing it. In the case of the prospective APR patient, doing nothing means a 75-90% chance of losing her wanted child. Giving natural progesterone results in an approximately 68% survival rate for her child. To withhold progesterone when a woman has changed her mind about wanting an abortion is tantamount to coerced abortion.

Given the evidence supporting APR and the lack of evidence against its safety and efficacy, an honest appraisal of the literature surrounding it should conclude that it is a rational and scientifically based approach to reversing the effects of mifepristone blockage of progesterone receptors using a medication with a more than 50-year track record of safety in early pregnancy.

Unless medical professionals are overstating the treatment’s success rate, there is no good reason for Colorado’s medical, nursing, or pharmacy boards to oppose the discussion of APR, especially to go so far as to make it illegal. In fact, as medical professionals, we should be focused on offering our patients fully informed consent: a description of any procedure they are considering undergoing, as well as its risks, benefits and alternatives. Neglecting to offer patients all relevant information is a violation of medical ethics. Thus, to ban medical professionals from discussing APR with their patients is to legally mandate that they practice bad medicine.

Conclusion

- While mifepristone reversal with natural progesterone is a relatively recent treatment, the evidence that currently supports it is promising.

- Critiques of the evidence supporting APR are deficient, blatantly misleading, or outright false.

- Considering that APR is a life-saving treatment, it is paramount that patients considering abortion know that they may have the opportunity to preserve their preborn child’s life and their pregnancy should they change their mind.

- Banning discussions of APR constitutes not only mandating that medical professionals fail to offer their patients informed consent, but also, in cases where a patient is requesting to stop a chemical abortion, amounts to coercing abortion for Colorado women.

Sources

1. Pelley, John W. in Elsevier’s Integrated Review Biochemistry (Second Edition), 2012 p 33-34.

2. Baulieu EE, Segal SJ. The Antiprogestin Steroid RU486 and Human Fertility Control. Proceedings of a Conference on the Antiprogestational Compound RU486. Oct 23-25. Bellagio, Italy. Published in the series Reproductive Biology 1984 Sheldon Segal Series Editor 1985 Plenum Press.

3. Yamabe S, et al. The effect of RU486 and progesterone on luteal function during pregnancy. Nihon Naibunpi Gakkai Zasshi. 1989 May 20;65(5):497-511. Attached as Exhibit B.

4. Delgado G, Davenport ML. Progesterone use to reverse the effects of mifepristone. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 Dec;46(12):e36. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R252. Epub 2012 Nov 27. PMID: 23191936.

5. Garratt D, Turner J.V. Progesterone for preventing pregnancy termination after initiation of medical abortion with mifepristone. European Journal of Contraceptive and Reproductive Health Care. 2017 Dec;22(6):472-475.

6. Delgado G, Condly SJ, Davenport M, Tinnakornsrisuphap T, Mack J, Khauv V, Zhou PS. A case series detailing the successful reversal of the effects of mifepristone using progesterone. Issues Law Med. 2018 Spring;33(1):21-31. PMID: 30831017.

7. Davenport ML, et al., Embryo survival after mifepristone: a systematic review of the literature. Issues in Law and Medicine (2017) 32(1):p 3-18

8. Mitchell D. Creinin, M.D., “Mifepristone Antagonization With Progesterone to Prevent Medical Abortion,” Obstetrics & Gynecology vol. 135, 158-165 (Jan. 2020) available at https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/pages/articleviewer.aspx?year=2020&issue=01000&article=00021&type=Fulltext.

9. Cirucci CA, Aultman KA, Harrison DJ. Mifepristone Adverse Events Identified by Planned Parenthood in 2009 and 2010 Compared to Those in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System and Those Obtained Through the Freedom of Information Act. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2021 Dec 21;8:23333928211068919. doi: 10.1177/23333928211068919. PMID: 34993274; PMCID: PMC8724996.

10. Progesterone: Risks and Benefits, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, available at: https://www.sart.org/patients/a-patients-guide-to-assisted-reproductive-technology/stimulation/progesterone/.

11. American Society for Rep. Medicine. Practice Committee Opinion: Progesterone supplementation during the luteal phase and in early pregnancy in the treatment of infertility: an educational bulletin. Fert. Steril. (2008). 89 (4)

12. Coomarasamy A, Devall AJ, Cheed V, Harb H, Middleton LJ, Gallos ID, Williams H, Eapen AK, Roberts T, Ogwulu CC, Goranitis I, Daniels JP, Ahmed A, Bender-Atik R, Bhatia K, Bottomley C, Brewin J, Choudhary M, Crosfill F, Deb S, Duncan WC, Ewer A, Hinshaw K, Holland T, Izzat F, Johns J, Kriedt K, Lumsden MA, Manda P, Norman JE, Nunes N, Overton CE, Quenby S, Rao S, Ross J, Shahid A, Underwood M, Vaithilingam N, Watkins L, Wykes C, Horne A, Jurkovic D. A Randomized Trial of Progesterone in Women with Bleeding in Early Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 9;380(19):1815-1824. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813730. PMID: 31067371.

13. Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Jul;128(1):305-310. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171. PMID: 21701348; PMCID: PMC3124652.

14. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 613 (Nov. 2014) (reaffirmed 2019).